Cost of Rationalism

The post-Enlightenment era saw the rapid dissemination of rationalism around the world. By thinking with reason, and using the scientific method, we have made countless new discoveries and inventions over the past few centuries, far beyond what any person from the Middle Ages could have imagined. This unbelievable yet undeniable speed of progress acted as an immensely powerful force, and propelled rationalism to become the dominant philosophy practiced in the world. Without a doubt we now live in the Age of Reason. Of course, this doesn’t mean that people are rational, only that rationalism is revered as the pinnacle of intellectual thinking.

But like all good things, this dominance of rationalism in the modern world does not come without any cost. One of the bigger costs that we paid, and the one that I want to examine here, is that we are now more dismissive towards things that we do not fully understand, and are less likely to engage in or utilize them, even when they could be beneficial to us.

A few clarifications before we dive deeper into this. First, this downside is not necessarily due to rationalism itself, but rather a product of rationality being in the position as “the best way to think” in modern society. Whenever a style of thinking becomes too dominant, no matter how good it may be on its own, there will likely be some undesirable effects, such as missing out on other approaches to thinking, or people misusing it. Second, even with this cost, it still doesn’t mean that the dominance of rational thinking is overall bad. Nothing is perfect, and despite the potential flaws, a society where rationality and reason is the default modus operandi for intellectuals is probably still better than any known alternative. What I want to do here is more of a meta-epistemological analysis of this particular flaw, to see some of its consequences, and to be more cognizant of its effects.

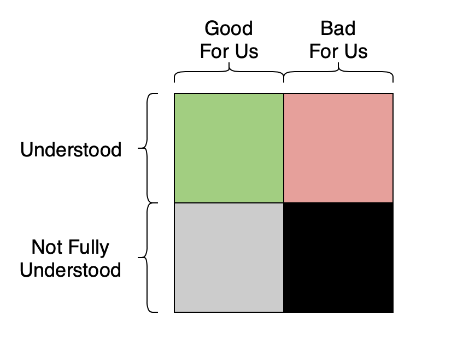

We can divide the world into things that we fully understand with rationality and reason, and things we do not yet fully understand. Along another dimension, we can see that some things are (taking the overall net effects) beneficial to us, and some are harmful. Putting these categories into graphical form, and ignoring their relative sizes, we get something like the following:

The top left corner (in green) represents the things that we have a pretty good understanding of, that are beneficial or useful to us. Things like the germ theory, Newtonian dynamics, and the various types of vitamins the body needs. The top right corner (in red) are all the things that we know fairly certainly to be harmful to us, such as smoking, excessive consumption of sugar, ionizing radiation, etc… The bottom half of the graph is the infinite set of things that we do not yet fully understand, which could be good or bad for us.

Rationality and reason have, throughout the ages, greatly expanded the size of the top half of the diagram. Reason has conditioned us to seek understanding first, before action, because there are a lot of things in the right side of the diagram. Today, with rationalism reigning supreme as the most dominant way of thinking, we tend to be more skeptical of everything in the bottom half of the diagram. This helps us avoid the harm of things in the bottom right square, but at the same time, causes us to miss out on the benefits of the things in the bottom left corner. The decline of religion, and of the various non-western alternative medicines/techniques are some prominent examples of this shift.

Why do we have more trouble taking advantage of the good things that we don’t understand? There are many reasons, but a couple stand out to me.

First is that we have a tendency to mistake the lack of evidence of benefit for evidence of no benefit. The world is full of extremely complex things that are simply beyond our comprehension. It is very difficult, and often impossible to show, with the rigor required to satisfy that of a rational thinker, just exactly how a complex system functions, what are its exact effects, and how it is beneficial to us. It’s easy for us to confuse this failure to understand as proof that this complex system has no positive effects, and as a result we treat it as if it’s useless.

Then there is our inherent fear of and skepticism towards that which we do not understand. Modernity has made it so that we no longer have to deal with the chaos of unknown on a regular basis. As a result of this, we have become complacent, in a sense, and have developed a habit to avoid the unknown, the unexplained, and the unarticulated.

That said, we do have ways to capitalize on some of the good things in the bottom left corner of the diagram. There are things that are complex beyond our understanding, but that we cannot reasonably avoid. The free market economy is a good example of this. In order to reconcile the need to participate in the economy with our skepticism towards the unknown as driven by our rationality-dominating minds, we attempted to create explanations, with various frameworks. These frameworks, such as the various theories in macroeconomics, are often wrong or incomplete, but they at least gave us the illusion of understanding, so that we can engage in these activities and reap their benefits without completely freaking out. This is a very powerful technique, and in recent years, a number of people have gained insane popularity by using it on things that we have not tried it on before, such as various religious beliefs.

After recognizing this price that we paid for the rationality-dominated modern world, one important thing to note that can help minimize that cost is to try not to dismiss outright things that are beyond our understanding. In order to separate the actual non-sense from what could be useful, we can look at the past for clues. With our tendency to seek understanding first and foremost, we sometimes ignore the apparent usefulness of things that is evident from their historic track records. What has survived the test of time, even if we cannot really explain why, probably warrants at least some attention.

Some people are able to do this better than others, and so can utilize more of the useful things in the domain of the unarticulated. Entrepreneurs for example, the people who found new ventures, have to deal with the unknown on a regular basis. Founders who are hyper-rational tend to get stuck in the analysis paralysis of what to do. Should I hire my first engineer, or look for a technical co-founder? No amount of rational analysis can give you a definitive answer to this type of question, and they quickly realize that sometimes a leap of faith based on intuition is the best course of action, and will simply adapt based on what happens. This intuitive gut feeling, which cannot be explained adequately by rationality and reason, is nonetheless extremely useful.